“An Interrupted History of Punk and Underground Resources in Turkey 1978-1999” researches the development of the Punk and underground movement in Turkey. With interviews with local bands and witnesses of the period and over a hundred visuals and the complementary CD, this book is the first of its kind and is a fascinating source on Punk and its place in Turkey’s recent cultural history. [Link]

Editors: Sezgin Boynik, Tolga Güldallı

Book Design: Ali Cindoruk

Publisher: BAS

576 pages (Turkish/English) + CD

ISBN 978-605-0025-00-2

9,1 x 6,3 inches

Being Punk in Turkey

Tolga Güldallı

According to the familiar and accepted encyclopedic definition of the term, Punk is an anti-establishment, subversive subculture that developed around a music movement in England in the second half of the 1970s to wreak havoc upon the values of mainstream society. Punk’s musical roots can be traced back to some New York bands of the mid-1970’s, while its attitude and style came from England. Over time, Punk’s nihilist and subversive attitude matured, transforming into a do-it-yourself destructive-creative, anti-fascist, anti-capitalist, anti-militarist, anti-authoritarian, anti-sexist, anti-homophobic, deeply ecological, pro-animal rights “ideology.”

In the second half of the 1970’s, Punk was an expression of rage in Europe and the U.S., while in Turkey, rage found its outlet in the form of street clashes, strikes and revolutionary rehearsals. In Turkey, it wasn’t yet the “time” for “listening to music.” The “traditional” military coup d’état of 12 September 1980 was accompanied by torture, dungeons, executions, exile, prohibitions, censorship and anti-democratic legislation. The regime of 12 September did a fine job of “shutting up” and “putting a lid” on the opposition, especially the Left, leaving behind a legacy of systematic apoliticization and dehumanization, whereby it succeeded in assimilating all segments of society, including universities and artistic communities. It was the age of “Uncle Özal,” “striking it rich,” “video cassettes,” and “arabesque.”

A space did exist for youths who refused to accept the degenerate arabesque culture imposed upon them and who sought some breathing room within this assimilated, dehumanized society; that “space” was called Heavy Metal. It was thanks to the hangouts where cassette tape copies of albums were made, and the “unsubtitled” pages of a few Heavy Metal magazines from abroad, that a certain group of youths who felt themselves to be “different” came to know Heavy Metal. For most, though, this introduction to the magazine world of Heavy Metal would evolve into something more, leading them to discover Punk music and thus serving as a point of departure in terms of “style” too, as they ventured into the realm of Punk in its many facets.

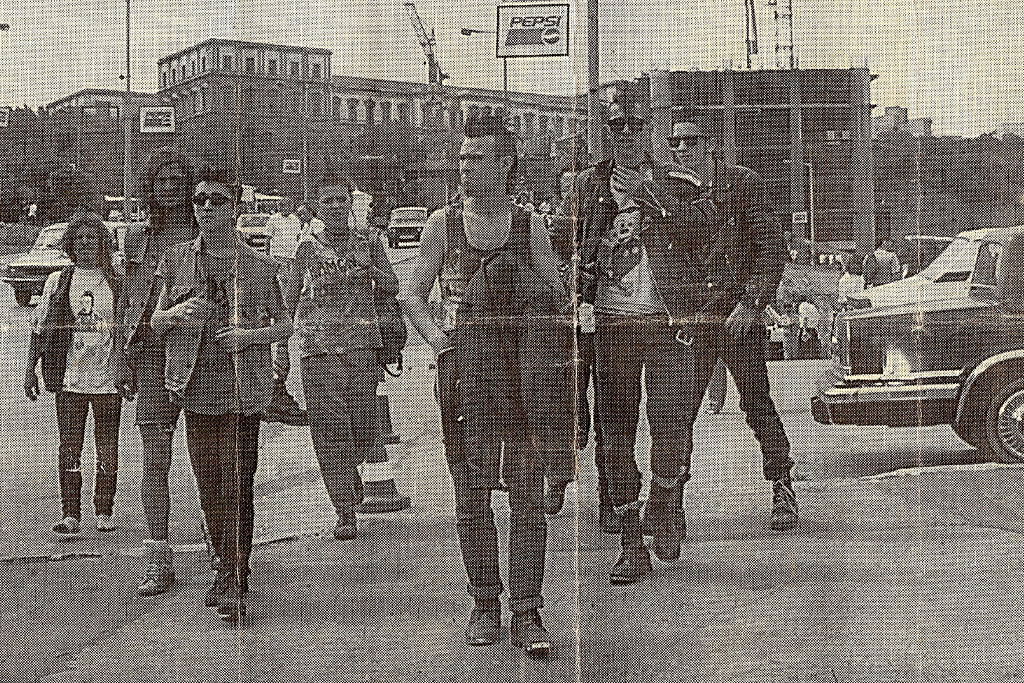

In the beginning of the mid-1980’s, those who identified themselves as metalheads or Punks became increasingly more prominent in daily life. The anti-establishment “shock” tactics employed by Punks in England around 1977, were manifested in Turkey too, in the late 1980’s, in the form of long hair, piercing, and ripped jeans -expressions of being “a free individual.” And that meant fights, day in and day out. However, other than such street woes, Punk failed to forge a cultural and/or political space for itself in the daily life of Turkey.

In Turkey, youth has never really had a say in anything, a fact of life in keeping with the general tradition and moral make-up of the country’s society. Due to reasons both economic and social, “youth habits,” such as belonging to a subculture, have been perceived as phases which are expected to last only up until a certain age (i.e., until you get a “real job,” or until the end of school, the beginning of military service, marriage, etc.) and which young people are expected to “get over” once they’ve “grown up.” Because relations with the Punk scene tended to be short-lived, it proved impossible to lay the foundations that would allow Punk culture and tradition to thrive; Punks therefore failed to create a subculture that would ensure a permanent, communal living sphere where they could express themselves and produce according to the DIY ethic.

There are numerous reasons why Punk failed to become political in Turkey. Foremost amongst these are undoubtedly the lasting, oppressive effects that the military coup d’état of 1980 had upon Turkish society, the conservative, insular nature of the post-coup Left as it sought to lick its wounds and carve out a new social space for itself, and Punks’ lack of enthusiasm when it came to participating in political life in general.

As is the case in many other countries, in Turkish society and media, Punk is often equated with perversion, a particular hairstyle, neo-Nazism, or Western wannabe-ism. Because of the lack of Turkish sources* about Punk, leaving Turkish readers with no other choice but to just “look at the pictures,” and the late, post-1990’s emergence of fanzines as a means of communication and knowledge-sharing within Punk, the concept of Punk has remained rather “shallow” even within the Punk scene itself. For the majority of those who have called themselves Punk, Punk never went beyond emulation, and Punk was never anything more than a kind of music, an appearance they were later forced to abandon, or the “delinquency” so often associated with the term.

This unfortunate state of affairs was not only true of Punk in Turkey of the 1980’s and 1990’s; it continues to be a problem, a “dead end,” if you will, common to all similar “youth subcultures” in this country. Though we cannot really speak of Punk as ever having been a widespread subculture in Turkey, we felt it necessary to document this era as it was lived here in an atmosphere of loneliness, impossibility, and desperation, in a depressive, conservative, “artificially colored” country, which has had its memory erased by coups d’états and lacks proper documentation of its history.

The book that you hold in your hands -the “first” book of its kind, a claim which, you are assured, serves as no source of pride- contains the musical and underground resources in which Punk in Turkey found concrete expression, from the 1980’s up until the year 1999, which witnessed the release of Rashit’s album Telaşa Mahal Yok, the first “official” Turkish Punk album. However, it should be noted that this book contains “certain” individuals and bands who were witnesses of that era, and that it should therefore not be considered “the authoritative and comprehensive account of Punk in Turkey”.

Another movement frequently mentioned in this book, alongside Punk, is Hardcore. Hardcore is a style created in the early 1980’s by Punks in the U.S. who did not “dress” like other Punks and who played music that was much faster than classical Punk music is, and which its followers dubbed Hardcore in order to distinguish themselves. Today, Hardcore, with its originality, discipline, and harsh expression, has become a core movement virtually synonymous with Punk itself. However, in order to avoid confusion over terms, in this book the word Punk has generally been used to signify both.

Not counting an occasional mention in magazine columns, the word “Punk” made its debut in Turkey in the year 1978, on the cover of a record by a band called Tünay Akdeniz ve Grup Çığrışım, who labeled their music Punk Rock. However, in this case, the expression was more of a “joke” intended to boost sales. The first band to actively play Punk in Turkey was Headbangers, which formed in 1987.

1991 was the year that witnessed the birth of the concept “fanzine” and the appearance of fanzines, the primary communication channels of Punk in Turkey. Punk music was disseminated via “demo cassettes” copied at homes, in keeping with the “do it yourself” ethic of Punk (whether naturally or “out of necessity”). In 1994, Radical Noise, Necrosis, and Turmoil broke ground in Turkish music when they became the first groups to have their records produced abroad (they had been produced in Turkey years before)…

No matter how much, in terms of its music and its “style”, Punk may have been domesticated, transformed, and packaged into a profitable product by capitalism, the truth is that Punk will thrive as an attitude, with all of its different dynamics and as a dissident subculture, with its underground spirit of sharing and community, so long as life goes on.

* Punks in Turkey were unable to access resources about Punk in the Turkish language until very late. The first book about Punk subculture translated into Turkish, Dick Hebdige’s Subculture: The Meaning Of Style, appeared in 1988. All other books on Punk were not published until after 2000. Of those, Tricia Henry’s Break All Rules: Punk Rock and the Making of a Style, which explains the musical and artistic movement that created and influenced Punk as well as the economic and social conditions that were the context for Punk’s emergence, and Craig O’Hara’s The Philosophy of Punk: More Than Noise! about the philosophy of Punk, are recommended titles.

On Punk in Turkish

Sezgin Boynik

1. Showing Your Left Ear with Your Right Hand

There is something very valuable that Punk could teach us, especially to social scientists and theoreticians: simplicity and immediacy. It teaches us how to speak the word without protracting, beautifying, evading, glorifying and fearing. There is another world culture that can teach us the same lesson and that is anarchism, which is most of the time the synonym of Punk. Yet, since anarchism is more of an issue of culture in comparison to Punk, its simplicity is inclined to be easily blurred by Lacan or Deleuze. Thus today we should search no more for simplicity and immediacy in anarchy. There are two reasons not to do so especially in Turkey. The first one (the historical explanation) is the systematic counter propaganda of the fascist culture industry, which since the 70s used the word anarchy in the most degrading meaning possible. (It is enough to take a look at the titles of the books printed in this period; “Anarchy from the View of Islam and Its Cures”, “The Chaos of the Universe: Anarchism”) Anarchism has become obsolete; if a bit of cynicism is allowed, it has become a “infantile disease”. Yet the second reason is more subtle, more devious and naturally more cultured. That is the greatest blow to simplicity. This time radical thought has become obsolete not because it has been blemished but because it has been made more complicated. This complicatedness means showing your left ear with your right hand; with the influence of the Baudrillard fashion (interesting enough this fashion was also evident in many fanzines) and of Deleuze, Zizek and then anti-Zizek and various post-modern thinkers, the possible simple immediacy of anarchy has turned into a deadlock. I think we can find the opposite of this attitude, which supports this situation and which turns the simplicity of anarchism (abolishing the state) into a grammatical spectacle, in Punk.

I believe that we can do this not by understanding Punk as a political movement but rather by thinking simple. As we have said before Punk means simplicity. The same thing should be emphasized once more; in many places around the world and especially in Turkey, anarchist theory has become something quite strange. Elusiveness and complication have joined forces with grammatology and destroyed anarchy’s transforming value. Because as we have shown it has become obsolete. If we picture the anxiety caused by not being able to understand and the boredom experienced by the readers faced with this discourse, the picture becomes clearer; for instance imagine a young anarchist trying to understand an abstract writer and getting bored.

Yet while criticizing blurriness, we have almost completely complicated the issue in favor of simplicity. In the end, we are talking about popular culture which is Punk and about modernism keeping in mind early Brecht and Benjamin who believed in the revolutionary power of popular culture and simplicity. When we interpret Punk from this perspective, we liberate it from the post-modern idea of it as fun and hedonism, and open up a new possibility of understanding the world. For me the importance of Punk lies in this potential.

In this introduction, which can be perceived as a eulogy to simplicity, I wanted to underline why I found Punk interesting philosophically and emphasize that if I was interested in Punk in Turkey or anywhere else, it was only because of this simplicity and immediacy. (I also need to state that I totally agree with Halil Turhanlı’s commentary on simplicity but since that critique of simplicity is more about form, it doesn’t concern us here.)

In the following pages we will see it it in more depth but probably it is not hard to guess that in Turkey a song so direct, so simple, so clear and so aggressive as “Suratına İşemek İstiyorum” (I wanna piss on your face) could only be sung by punks. What our theoreticians and social scientist can learn from Punk is a strong theory that wants to piss on faces. Of course this book was not written to produce such a theory. This is a book about Punk in Turkey. But while preparing this book we somehow carefully abstained from being intellectual at least as far as our approach and options were concerned.

Hence this book should not be read as a sociological case study or a “schizo-survey” or an oral history project. The research we have conducted in the process of preparing this book (usually interviews) was not done according to any methodology. This approach, which is as personal as can be, helped me a lot in understanding not only Punk in Turkey but also life and people.

2.Making a Cow out of a Crow Modernization in Turkey, which anyway has been a top down process from the start, has followed a very discontinuous course due especially to the military coups that took place almost every ten years. You don’t need to be far-sighted or very smart to understand that modernism is an unfinished project here.

Hence it can seem to seek for the traces of Punk in this history of Turkish modernization little strange, to be more exact, it is strange.

In the prior section, we actually treated Punk almost like a philosophical category. However aside from that, Punk is also a subculture movement that has a certain history and that has been seen predominantly in a certain geography. How can a movement that is accepted to have officially started in 1977 in London be understood in Turkey?

Because we do know (or more accurately it will be known through this book) that it was in the year 1987 (plus/minus 1 year) in Istanbul with the band Headbangers that Punk has gained a public meaning in the fullest sense, for the first time in Turkey. If we don’t take into account the imported “Punk Rock” of Tünay Akdeniz ve Çığrışımlar, then in Turkey, Punk has started 10 years later than it normally should have. The first official Punk album on the other hand was released almost ten years after that.

In this book we dealt with people who have concerned themselves with Punk in between these two dates in Turkey. The interviews and some of the articles in this book will give the reader an idea about this unknown history; I don’t think that anyone needs further specialized sociological interpretation.

Still a couple of words on methodology and the course of research; preparing this book proved much more difficult than I thought it would be. There can be several reasons for that; unwillingness, unfaithfulness, impatience or laziness on the part of the people we interviewed; the claim of most of the people we interviewed to having not much to say on the subject (though every time it was proved to the contrary); various psychological difficulties (like amnesia, remembering wrong, exaggeration or other things that can be explained with the effects of chemicals or changes in the political stance); and physical difficulties (like the lack of documents or the difficulties in accessing the people we wanted to interview). The total lack of documentation on the subject was the primary difficulty. Yet from the very beginning we tried to avoid a common mistake seen in “underground” research of this kind; “making a cow out of a crow.” Our aim was not to create a new urban legend with no reason

Punk easily lends itself to something like that, both as a philosophical category and as a historical phenomenon. Punk can have a different meaning in every place and every situation. For instance, it was a sign of tolerance that supported the theory and the practice of the Third Way theory of autonomous socialism in ex-Yugoslavia (think of the first and the best film of Emir Kusturica “Do You Remember Dolly Bell?”; only the hero in the film was playing not Punk but Rock ’n’ Roll). It was one of the pluralist nationalist voices in Latvia in the course of independence (the movie “Is It Easy to Be Young?” by Jri Podnieks). But then again, Punk is revolutionary, anti-authoritarian, aggressive and critical in relation to its time; it is also a Western, urban, elitist and against kitsch culture. Today, searching for traces of Punk and finding its followers in even the smallest and most underdeveloped of places can also be a sign of the unbounded influence of this modern/urban culture. If there are punks in Iran, their noise goes to show that there are voices other than the ezan (call to prayer) of mullahs and this noise guarantees that there is a modern urban culture even “there”. Hence to guarantee this, in many situations and places, people resort to the tactic of “making a cow out of a crow”. Thus a nonexistent history and a nonexistent tradition are invented.

In this book we tried to avoid this -at least as much as we can. Yet at the same time it is necessary to state that this research is not a Sherlock Holmes case.

Luk Haas follows punks all over the world and his report on Turkish Punk Community appears in this book. Can the practice, which he kept up for years with his label Tien An Men, be regarded as a case of “making a cow out of a crow”? Some people think yes, this is the last stage of exoticism: Hard-core Punk in Tajikistan! (It must definitely be an oxymoron!)

Yet since we believe in the sincerity of Luk Haas and his practice (putting into circulation the underground products of the Third World without utilizing any big mainstream channel, preparing all his products by himself, DIY, etc.), we presume that there is no cynicsm in this example and that his records are no more dangerous than their material vinyl. So much for Luk Haas.

The argument we have just started on Punk being the guarantee of modernism and urban culture is very crucial; because in some cases Punk can also be a lakmus paper for multi-cultural, democratic, tolerant and “open societies”. If we caricaturize, we can say: “Ok, if you had Punk in even your darkest and most depressing times, then it is easier for you to be European.”

The existence of Punk in Turkey, especially its existence in the 80s, can be retroactively interpreted as a sign of political correctness and as something which guarantees that Turkey is a modern and open society. If we present Punk to be different or to be more than it really was by “making a cow out of a crow”, then we can easily become a spokesman of the neo-liberal view. Since this book is published with foreign funding, we should warn our readers even more in this respect. True, Punk can paradoxically be the voice of high culture (just like poor dead Debord can be a French intellectual) but we neither have any agenda (explicit or implicit) in this book, nor have we used Punk as explanation in any way.

If you let me, I want to pee in your theories -both on the complicated ones and the ones of conspiracies!

2. Not a Hammer, Not a Mirror, But a Window

Karl Marx’s assertion that “art should not be a mirror but rather a hammer” does not really hold for Turkish Punk music. Punk music in Turkey is a window. We will slowly prove that throughout this section.

When Punk had become a subculture movement widely known and popular among youth in London, Continental Europe and USA in 1977, the articles written in Turkey on Punk in specific and Rock ’n’ Roll in general were of a critical kind. Punk was synonymous with imperialism, Western decadence, decay and apoliticism. Those who criticized Punk were aware that it was an agent and a warrantor of Western democratic capitalism and that it could go hand in hand with the IMF (even though it appeared to be opposing it). In 1977 in Turkey, the Leftist movement was as far from Punk as can be; yet it was more radical than the most anarchist versions of Punk. At the same time, it was more internationalist than Punk in Turkey could ever be; at that famous year, Yar Press was publishing the manifestos of the guerilla movements of numerous countries including Italian ‘Brigate Rosse’ (Red Brigades), German ‘Rote Armee Fraktion’ (Red Army Fraction), Iran and Cambodia with the most modern of book designs. Militants and sympathizers were following the Leftist theory and practices of all the countries including Albania, China, Cuba and Bulgaria.

But the music of the Left was never a hammer; more accurately it was not a noise generating 3-chord annoyance in the sense understood by Punk. The music of the Left has either been the strong macho voice of male peasants or the thin voice of the female mother whining with melancholy. Political music in Turkey has always been that way; consecutive loses have even intensified this fatalistic tone of its. No matter how internationalist the Left had been in theory, it has remained at least localistic (gecekondu type!) in practice.

It seems to me that a melancholic Left voice cleansed of noise can bring with it a strange kind of conservatism. So much so that today if you visit radical political formations like Autonomists that are nourished by quite a bit of international theory (from Negri to Balibar), you should be ready for the most dated and dullest folk music of the world. Hence the Arabesque-Punk comparison made by Murat Belge in the early 80s is actually wrong. If we interpret Arabesque -as a Vox Populli with revolutionary potential and an amateur voice in opposition to high art music- to be synonymous with Punk, then we reduce the noisy simplicity that is the foundation of Punk to just a conservative outcry. Leftist music was not a hammer but it was also definitely not a mirror. Probably, mirroring and middle class psychological problems and depressions in music were started in the 80s by Sezen Aksu, and the dumbest liberals who still follow that trend.

But in the 80s, there also arose a voice from the youth which was not leftist, and was, for that reason, apolitical but was not the least middle class or mediocre either. Though this voice was of course raised initially with Heavy Metal, soon it acquired its real radicalism with Punk. We can see what kind of a place Turkey was in the 80s from the interviews conducted with people who lived here in this period; black outs, constant oppression, lack of clarity in everything, a weird and disgusting style, conservatism and savage capitalism. In that period, Punk was one of the rare radical movements that did not act as a mirror; and since they were not Marxists, they also didn’t have the chance to be hammers.

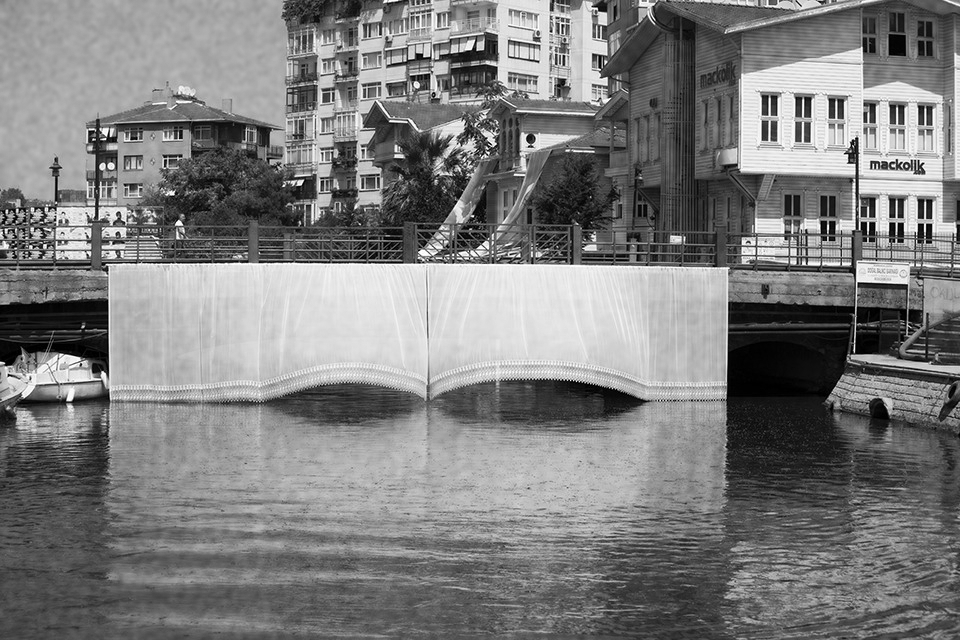

Besides, the number of Punks was very small at that time and the typical “underground” party proceeded as follows: a couple of Metal bands, then a Punk band and a break dance show in the middle, all performed in day time and at a rented wedding hall. As far as we can understand, underground culture of the period was trying to find itself anew after that amnesia of the 80s; thus no one could identify himself exactly as a fan/performer of Metal, Punk or Hard-core. Because of the shortcomings in Turkey, this period of search could also turn into something funny like the party mentioned above. Hence, while we explain the emergence of Punk in Turkey with that (dark) political and cultural environment of the 80s, we take into account that Punk was opposed to this situation. punks were young people who were tired of the melancholic Left of their parents, of the depression Pop around them, of being local and national and of self-enclosure. They were definitely willing to learn about new alternatives and to try out new things; if we really need to say it, they wanted to open up. Thus liberalism and the figure of Turgut Özal were hanging like the sword of Damocles over the dark side of Punk (like all else in Turkey). Özal, whose name is mentioned a couple of times in this book, is a troublesome name for the theory of opening up. Because both punks’ will for emancipation and Özal’s liberal Capitalist market program can be interpreted as reflections of the same wish of opening up and belonging to the world. Let’s not forget, the first Istanbul Biennial and the formation of the first Punk band took place at the same year. While promoting liberalism and savage capitalism with his will to open up, Özal was also supporting the most backward and the most conservative culture, with the same level of determination. For punks, this culture of opening up is different; it is to understand the world without the mediation of any official representation. Since this opening up could never be realized thoroughly -in the sense of getting rid of provinciality and localness (we will see the conditions under which this is possible in the following section)- we can see this take place more in the form of looking outside or taking an interest in the outside. Here, again, we should be careful not to reduce Punk to a spokesman for open society. We can leave aside this reductive interpretation very easily because punks in Istanbul did not worry or make plans about how the society could become a more suitable place and the Punk attitude had nothing to do with representing the country more openly. This resolution does not mean that punks cannot be interpreted in this way by others; at least we won’t do that even if the name of Özal and Punk come dangerously close to one another in a couple of places throughout this book. We can describe the theory I developed above in the following way: punks don’t have a problem of representation but they are problematically susceptible to being represented.

However, as readers will understand through this book, there was an incredible mass following what was going on in the world from the late 80s till the early 90s (pre-internet era). Even if small, this mass of people who became knowledgeable about the demos and fanzines all over the world by way of letters, still represent a possibility; the possibility that an alternative and critical urban culture in Turkey can exist. For some people, this window was going abroad, exchanging letters with people from abroad, for others it was the shop of Deniz Pınar; yet whatever form it took, it sure opened up to a different world.

That’s why we define Punk art as a window, because punks are searching for something other than their boring parents and the dumb politicians. This searching and learning process can of course create very funny outcomes. For instance, the imported Punk of Tünay Akdeniz and his synthesizing of this with abject entrails and fashionable safety pins will probably remain as a prototypical Punk comedy. Turkey’s history of opening up is full of examples resembling the hero of Araba Sevdası (Love for Cars): from the “helter skelter” of Barış Manço ve Kaygısızlar to the movie Şeytan (The Devil) by Metin Erksan. I guess the funniest one, which was as dangerous as it was funny, emerged in the interview we conducted with the vocalist of Dead Army Boots, Tarkan. When we asked him why he used swastika and gave a Hitler salute in one of his concerts, the old Punk replied that then Turks needed to do Turkish Punk, Germans German Punk and Americans American Punk. Then we reminded him that Dead Kennedys always did anti-American songs. Tarkan’s answer was the most interesting part of this story: “We were Dead Kennedys fans, we knew all their songs by heart and we also hated America.”

Like Marx said, sometimes understanding can be misunderstood. Since punks do not give a damn about political correctness, it can be an exaggeration to claim that this example is as dangerous or nationalistic as it seems. Anyhow we can multiply these Felliniesque examples as much as we want; after all we are talking about the Punk of a late and different modernization.

3. Selling Snails in a Muslim Neighborhood

This saying with its obvious conservatism points towards an impossibility in Turkey; not being able to be totally Western. At the same time, it cynically criticizes Westernism or Occidentalism if you will.

You can easily figure out from what we have told so far, the reason why Punk and other subcultures in Turkey are compared to the act of selling snails in a Muslim neighborhood. These same reasons also reveal the true nature of conservatism: that the social and cultural reality of Turkey is different from the West, and the myth around “it cannot be enough”. National values plus cultural anti-imperialism equals to this ambiguous conservative consciousness. As you might guess there is no place for Punk here. I don’t want to develop an opinion on how the categorical, historical and political possibilities of Punk discussed above can provide an alternative to this situation. Anyway I believe that only a Punk developed in a laboratory environment can accomplish this; moreover, I think that such an agenda will totally destroy the essence of Punk.

However in handling the issue of Punk, we can approach the subject from a totally different perspective; from the opposite of Occidentalism or more accurately from the view of Orientalism. Thus we can revisit the question we left unanswered in the preceding sections; under what condition can a Turkish Punk/Underground band open up to the world and become a part of world culture? It can do so only as long as it remains modern on the inside and traditional/folkloric on the outside. When examined from the viewpoint of Orientalism, Punk and other similar music and lifestyles that originate in Turkey should be of Turkish cultural (or more accurately, folkloric) origin. If a Turkish Punk band is willing to be successful, its music should definitely be spiced up by sa” or zurna, or contain an archaic rhythm structure. Otherwise its music will not have any meaning. Or as the Turkish underground music specialist Jay Dobis with whom we conducted an interview states: “It won’t be interesting at all. When there is such a rich folk music culture, why not use it? The Brits and the Americans are doing enough of this (underground); why to add more of the same thing?” Though they did not take it this far, we know that DJ John Peel, Tim Hodgkinson and Thuston Moore also took an interest in “oriental” tinted Turkish underground and Punk in general (but then again no one was specialized and clear enough as Dobis who gave “saz” counseling to Punk/Underground bands).

The most hilarious version of this is the limitless talent of Turkish bands in synthesizing East and West. The latest movie shot through the eyes of the bassist of Einstürzende Neubaten presents this in its most hideous and intolerable way; underground musicians of Turkey, of Istanbul have evolved into something really shallow with their worries of saz, klarinet and synthesis. Actually the poor old Piyer Loti Hacke could not see a serious alternative in Turkey even if he wanted to; because the music and subculture scene in Turkey has been subjected to total auto-Orientalisation. Most of the bands on the market are competing with one another to synthesize neo-psychedelic hippie post-rock confusion and the beautiful multi-cultural folk sounds of their country. Underground bands are usually defining the novelty of their music as being situated somewhere between The Can and Müslüm Gürses, or Velvet Underground and Orhan Gencebay and they don’t fear that this synthesis can evolve into something most conservative.

I could examine how this situation arose and make a good cerebral exercise by dwelling into the available post-colonial theories but there are two instructive bands/phenomena that document this transformation in Turkey very well: Zen and 2/5 BZ. Both bands started around the same time (end of 80s and beginning of 90s) and they did avant-Punk and experimental music in a political fashion (something non-existent in Turkey). Yet by mid 90s, they slowly left aside the guitar and gravitated towards the saz and while rediscovering the richness of the folk melodies of their own country, they both reduced the noise of their music and approached a performative sound mythology in the name of synthesizing. Zen changed its name to Baba Zula and after their latest album Tanbul (again with saz) they completely advanced being oriental and became the most successful Turkish band to synthesize “belly dance, Punk, Dada, Psychedelic and Dub”. Meanwhile though the band 2/5 BZ is trying to conceal this oriental condition with a fake cynical self-criticism “no turistik, no egzotik”; we can see that they have no relation whatsoever left with their earlier work. (Here the hats are off for Bülent Tangay!) The relation of these two bands and of many other formations that follow their lead to Orientalism should be analyzed more seriously; however here we should at least mention this much: we can’t help but notice that there has been a direct proportional relation between the orientalization of the sounds and attitudes of these two bands and the increase in the level of their opening up to the world and the respect they receive as musicians.

In this book we took a look at the sincere and strong underground sounds produced between late 80s and early 90s and that usually escaped the attention of most people. We hope that the readers become aware of a possibility, a possibility different than today; a possibility that belongs neither to snails, nor to Muslims.

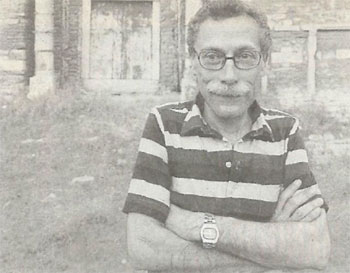

Kemal Aydemir – Interview

How did you get involved with Punk?

I went to England to study graphic design. When I arrived, I saw that the schools were incredibly expensive. The plan was this: I was gonna work part time and go to school for the rest of the day.

Which school?

There was no school. I couldn’t get into one. That “which school” never happened.

What year was this?

1977. There was hippie life going on in Turkey at the time, everyone was wearing their hair long. I took off from such a scene here and went there. The picture was a different one altogether. The hippies were older, most of them were living in squatted houses. After a while I started to be aware of the Punks, weird make-up, torn clothes, pins and stuff. You didn’t see them that often though, the year was only still ‘77. I thought that they were all wackos. I thought that they were psychos, thought they were dangerous. I was still thinking like a hippie you see, still listening to Pink Floyd, Frank Zappa. A friend said “these are the punks. It’s a new thing here. They have clubs. I’ll take you to one of their concerts and you’ll see the difference”. I said, “okay, let’s go.” We went there. There was this place called “The Marquee”. The Lurkers were playing there that day and 999 was playing as well. I went inside and I’m telling you, I was really frightened. Now we were quite decently dressed; they were all in torn clothes, chains and stuff. The club looked like an insane asylum. I started wondering what I was doing there and I was frightened, but on the other hand I really liked it. It was very colorful. The concert started, we were right there in the front row, and they were letting people drink beer. They started doing pogo and all… you should have seen the commotion. People were on top of each other, they were spurting and spitting beer on each other. Everyone was soaked with beer. We were scared that there would be a fight, so we went towards the back of the room and started watching from there. There was an incredible energy in the music when I first listened to it. I don’t quite know how to make a comparison. Our groups from the ‘60s for instance, they take their places on stage, play a specific song and then a guitar solo starts and goes on for hours, jar jur jar jur. And then enter the drums and that’s it. These guys were playing one song for two minutes and then, wham, the second song began. No guitar solos or anything, but there was an awesome energy as well. I said, “man, I love this music, let’s come here every week.”

We lived in North London at the time. All the houses were squatted there. There was also a very important pub in English Rock Music history that was there. Very important musicians played there and it wasn’t that huge place either. Since I was living in the neighbourhood I kept popping my head in to see who was playing. I became a regular of that pub. I said to myself, “drop the hippies man, there is life in these punks.” And afterwards, I mean, I still didn’t know what it was that these guys wanted, what their goals were, what their culture was like. My English was very bad so I really didn’t understand much. We used to go to Kings Road. Punks strutted up and down there. They’d dress up, folks would stare at these punks and the punks would spit at them and so on. Malcolm McLaren had a shop there, it was called “SEX”. I was passing by one day, but I didn’t know that it was a shop. They put an army boot on display in the window and it rotted there. I didn’t have the slightest clue about conceptual art and stuff either. I thought “what is this place?” I went inside and there was Jordan, staring at me with a whip in her hand. I thought “oh no, this can’t be good.” However, I really liked the shop. No one pestered me like they do in the other shops. And the music playing was Punk. I thought “This must be a Punk shop.” And then I looked at the clothes and stuff, which were all fetishistic. Bondage trousers were in at the time. Who the hell would wear these? Then I looked at the t-shirts. First thing, I really liked the designs on them, those phosphorescent colours and all. Whenever I went to Kings Road I’d drop by the shop. Then some time passed by. punks were not allowed to play their music. I was checking the newspapers. It looked like the Sex Pistols were playing, but no one knew where. They were playing undercover. Something happened: In one of the concerts someone threw a bottle at a girl and it poked one of her eyes out. All Punk concerts were banned. We kept going to The Marquee, but there were no gigs going on. They were distributing flyers saying there will be a concert at this place, this time etc. One day I went to one of those. I showed them the flyer I was given and they just let me in. It was so crowded inside. The building looked like an old factory or a warehouse. I still thought that in a concert there would be seats and everyone would be seated and stuff. I looked around, the place was full of punks. I was wearing a raincoat. While I was still wondering to myself “how are they going to give a concert here?” they came on to the stage – the Sex Pistols. Well, I didn’t know that they were The Sex Pistols because they appeared under other names as well, from time to time. For instance, even when it was The Sex Pistols on stage they would be announced as The Adventurers, so they wouldn’t get caught, they were banned from playing. Anyway, one of them appeared in doctor’s scrubs. It was hellish. There were these people called skinheads at the time and they were fascists, they were against Punk. They didn’t like it. They raided the place, all hell broke loose. A guy lashed a razor at another and caught him on the lip. Police cars and everything. I threw myself out on to the street. I said, “Man, I will never go to one of their concerts ever again.”

You were there at just the right time when Punk was happening. How old were you?

Twenty-five at the time. To tell you the truth, I was a bit old for those punks. They were all 16-17, 20 at the most.

Were all the listeners of Punk English? Were there any other foreigners?

At the beginning all listeners were English. At the end of the ‘70s and at the beginning of the ‘80s, girls and boys dressed as punks started coming from France, Denmark.

Were you discriminated against when you told them that you were Turkish?

Punks never had any racism in them. Clash even did something, launched a campaign called Rock Against Racism.

Which concerts did you see?

X-ray Spex, Siouxsie and the Banshees, The Lurkers, I saw almost all of them. A brand new door was opened with Punk during the ‘80s. In the oldies, you know, there was always this love thing going on and that finished with Punk. The songs were an expression of rage from then on. After Punk there came Industrial Music. Around the same time something called Two Tones Ska emerged. You see, it was the period when London was flying higher than it ever did before. And then there were the new romantics, around the same time as Psychobilly. I mean during that period they were all playing in different venues. And then there were the Teddy Boys who still listened to ‘50s Rock ’n’ Roll. I was living in London when everything was booming beautifully. I caught up with Punk, New Wave and all the other waves that came after. Joy Division and all. Some dark music… Sisters of Mercy. It completely changed the way I saw the world. I was squatting myself, most of the time. You could do that then – you could go, break the door and enter a building, and it’s yours. There was a law in England for that. If you don’t have a place to live in, you just break your way into a building, change the locks, and after that you go to the council and you tell them that you didn’t have a place to stay so you are staying in this building now. You have them reconnect the electricity and you pay for it. You don’t pay rent though. Squat. The people who squatted were mostly hippies, punks and gothics.

Were you playing music when you were there?

No, no. I did all sorts of lousy jobs there. I worked in construction. Worked in a restaurant, washed dishes back in the kitchen.

Did you have a residence permit or were you staying illegally?

I forged a marriage on paper. I was caught and extradited.

And what did you think about Istanbul on your return?

Don’t even mention it, man, that was the worst part. I came back and saw that the country was under martial law. Man, I landed at the airport and I saw that the place was swarming with soldiers and machine guns. I said to myself, “I must have landed someplace else by mistake. What is this place, Africa or what? This can’t be Turkey.” You come from a free country and all you see is soldiers everywhere. “Go,” a soldier was shouting, “get your paperwork done.” He said that there was going to be a blackout at two o’clock. I said, “Oh no, what blackout?” He said that the curfew would begin soon. He said “man, quick, find this guy a taxi cab.” I had two cases full of records. If they saw the records they’d definitely arrest me, because those things were banned at the time. For instance, if they found Alien Sexfriend’s record inside they definitely would tear it apart and toss it. My brother used to work there, so I didn’t let them check my luggage. So when I came back to Istanbul, I sank into a deep depression. Six months passed. I couldn’t stand it here. You know, you get used to the comfortable life over there. This felt really off. The system was too militaristic for my liking. I decided I should get out as soon as possible. On top of all of this they took away my passport. My, oh my, now what? Boredom and depression…

Well, didn’t you have any friends who listened to Punk?

No, none. Not even one. I was so lonely. I listened to those records, you see, I was young and it was the worst of times, I cried and cried. I was doing pogo at home, all by myself. I was devastated. No one listened to Punk over here. British Metal was emerging at the time. Sometimes I’d go hang out with them for a change. Punk? There was no one. I said Punk, they said “What the hell is Punk, man?” They didn’t like it, that’s all. Metal lovers didn’t like Punk. They thought it was fascist, but in truth it had nothing to do with fascism. I don’t remember any racist Punk groups, not one. There were even black guys. I don’t know maybe later on something different happened, but during the first years of Punk, between ’77-’80, I don’t recall any Punk groups that were racists. And I definitely wouldn’t get hooked up with them if they were. A guy called Hakan had a stall on the plaza right next to the train station. I had this crazy thing that no one else had. I used to bring tapes to him and I would force him to play them out loud. “Man,” he would say, “cut this punk stuff out. It doesn’t work for me. I am a Megadeth kind of guy.” They thought the guitar solos were too light and that’s why they didn’t like Punk. He would see me and say, “Oh, no. Not you again…” Lots of time passed until I met the punk kids in the ‘90s. I met them. They told me that they had their own group, that they listened to Punk.

Who do you mean by “they”?

Noisy Mob.

Which year was this?

Beginning of the ’90s.

Recently I’ve read an interview with The Headbangers. They talk about you. They say that they learned all about Punk from you.

That’s probably right. I used to tell them about it sometimes. The kids were asking me, what is Punk and so on. I used to tell them there are bands called this and that, there is this music. Then the impact of Punk slowly started reeling in from abroad. There were neither many listeners, nor sources.

What were you listening to at the time?

Apart from Punk there was Gothic, Industrial. The Test Department group, Foetus, Clock Diva and many others which I can’t remember right now. And I sold them all to Deniz (Deniz’s bookstore) later.

How did you meet Deniz?

I really don’t remember. We always went to Narmanlı Han at that time. It was a meeting point, it was always crowded. There was nowhere else to go. Everybody went to Deniz’s shop. The newspapers printed stuff like… Esat was publishing a magazine called “Mondo Trasho” all by himself. Some people were curious, what is this Mondo Trasho? They were hanging around at Deniz’s shop.

Did you know Esat?

No. I met him here. In fact I saw the magazine. I loved it. I thought “what a beautiful magazine.” There were other fanzines, but I didn’t like them. Some guy wrote ten pages of poetry, for example. When I finally met Esat, I told him he was doing a great job and asked him how he did it, because I was surprised. Really, if you’ve never been abroad, there are certain things that you can’t know, whatever you do. There was no internet at the time. Turkey was still a closed-up world on its own. No magazines, no books. Naki Tez, Murat Ertel, Gamze Fidan, Nalan Yırtmaç, and there was this boy, a photographer, I don’t remember his name. The circle was quite crowded in fact. There was one circle around mondo trasho and another around Deniz. The mob from Bakırköy had their separate circle and there were those who came from Kadıköy and these guys were Ismail’s mob, The Headbangers.

What about friends you’d got here before you went to England? Did you get in touch with them after your return?

No I didn’t. Most of them died during the drug epidemic in the ‘60s or most of them ran away because of the terror here. They could not stand it. During the ‘70s long hair was not tolerated here at all and bell bottoms weren’t either. We were completely out of it, man, trousers with patches on them and stuff. The life here was really hard for guys like us. Most of them ran for their lives, went abroad in search of freedom. I’ve scarcely seen anyone from my youth.

✪